I have a goal to attend a baseball game once a month this summer and I’m happy to say I’m hitting above average. Last week, I was part of a group that went to Camden Yards to watch the Os play the Blue Jays and before we went, four of us were tasked with writing shorts on what makes the game great. I’m grateful to these writers for sharing their words here—you’re in for an all-star lineup.

Three Things to Love about Baseball

By Josh Noem

One: Baseball is a sport built around failure. If you hit the ball and reach base once out of every three at-bats, you're in the Hall of Fame. In 240,000 major league games throughout history, there have been only 24 perfect games where a pitcher faces 27 batters and retires each one in order. The game teaches humility and detachment—to succeed, players must become familiar with making mistakes and learn how to have an open hand about both success and failure. Just watch a batter after he strikes out—observe his walk back to the dugout for a good two minutes. Or examine the pitcher when a batter gets a big hit—how he collects himself to face the next hitter. More often than not, you'll see resilience born of humility.

Two: Baseball is a good image of communion because it has a unique balance of individual and collective effort. The only offensive player on the field to start an inning is the hitter. If he reaches base, he needs help from teammates to return home—the individual contributor can only go so far. When the ball is put into play, only one fielder can make a play on the ball at a time. Still, each player is ready to do their part when the pitch is thrown, even though there's a very small chance the ball will come directly to them. Watch the feet of an infielder when the pitch is delivered—he springs into a short little hop at the moment the ball crosses the plate. He’s ready to instantly respond wherever the ball is hit. And if the ball doesn’t come to him directly, keep your eyes on him—he’s running somewhere in case there’s a bad throw or missed catch. A team can only be excellent together, even though the actions on the field primarily unfold on the level of the individual.

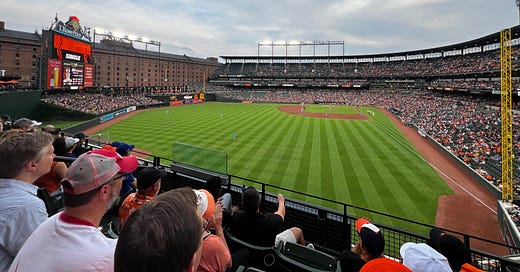

Three: Baseball was built for poor people. We call baseball "the national pastime" because it was a sport that served the working class during the Industrial Revolution. Factory workers in cities who needed leisure had precious few green spaces to turn to. When you enter a stadium, you'll find a moment when the field opens up before you along with the skyline and a great vacuous open space. Imagine that view through the eyes of a factory worker who would have spent all day inside, encased in steel and brick, surrounded by the constant, gnawing roar of machinery. To spend several hours in the fresh air with a green field before you, observing excellence on the field, and maybe, just maybe, a beer in hand—that's a slice of heaven.

How God Hangs Out

by Mike Jordan Laskey

“Almost certainly God is not in time,” wrote CS Lewis in Mere Christianity. “His life does not consist of moments following one another. If a million people are praying to him at 10:30 tonight, he need not listen to them all in that one little snippet which we call 10:30. 10:30. . . is always the present for him.”

How rarely in our lives do we get to exist outside of time. Maybe in the dentist’s chair, when 20 minutes can pass slower than six months, or on a particularly lovely vacation, which ends faster than you thought possible.

My favorite way to break the surly bonds of time is to watch a baseball game, or, if I can’t get to the stadium, to listen to it unfurl over three hours on the radio. Unlike basketball or soccer, baseball has no clock. The longest game in American pro baseball history was played over three nights in 1981 between the minor-league Rochester Red Wings and Pawtucket Red Sox. It lasted 33 innings, with 8 hours and 25 minutes of playing time. Baseball is nothing like the perfectly choreographed National Football League, whose games last a precise three hours. There’s no predicting when you’ll get home from the park.

The late Roger Angell, the unequaled bard of American baseball writers, wrote my favorite line about baseball’s lack of a clock: “Since baseball time is measured only in outs, all you have to do is succeed utterly; keep hitting, keep the rally alive, and you have defeated time. You remain forever young.”

Or, to my Catholic sensibilities, you get a chance to experience how God hangs out.

Mike Jordan Laskey is the communications director for the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States, where he manages the Jesuit Media Lab and hosts the excellent AMDG Podcast.

Catholics and Baseball

by Michael O’Connell

Some of the reasons Catholicism and baseball go together are immediately obvious—like the Church, baseball has its cathedrals and saints and relics and rituals. And there’s a lot about attending a baseball game that is like going to Mass. Because in baseball, winning a particular game is less significant than in almost any other sport—the regular season has so many games that any one outcome isn’t particularly important—it's the embodied experience of the game that really matters. Showing up. Being present for the sounds and sights and smells, and realizing that what we’re participating in at the ballpark is more or less the same going back generations. Going to a game can, like going to Mass, be an opportunity for moments of transcendence and communal joy.

Like I said, baseball has its cathedrals—old ones that go back almost to the beginning of the professional sport: Fenway Park in Boston and Wrigley Field in Chicago. But Camden Yards is special in its own way because it started the modern trend of baseball stadiums being awesome again. It’s probably stretching things too far to say that there’s a parallel to the ressourcement return to the sources movement in 20th century theology. But the idea of Camden Yards, which opened in the early 90s, was to build a modern stadium that felt like an old-fashioned one. In the 70s and 80s, new baseball stadiums were huge boxy boring affairs, with cookie-cutter designs built to host multiple events, but Camden Yards was deliberately made to be smaller and quirkier and explicitly and only for baseball. The designers wanted it to look and feel like an old timey park. They built it in an urban area, as part of a plan to revitalize the downtown. And people loved it, and it was the template for most of the newer stadiums built after it. So, architecturally, it’s a crown jewel of baseball, one that takes the best of the old and marries it to what we want and need that is new. And perhaps we can see a model for the Church in that?

And, finally, one last reason we as Catholics should be excited about the game: the players. To see someone play a sport at the highest level, to pay careful attention to how they use their body with perfect control and execution, can (to borrow a phrase from David Foster Wallace’s essay on Roger Federer) be a kind of spiritual experience. But this is baseball. So it’s always possible the players we’re excited to see don't actually play, or they will play poorly—go hitless, commit errors. I’d say this too resonates with the spiritual life. We might do everything to prepare ourselves for an experience of grace—put ourselves in the right mindset, carve out sacred time and space—and still nothing happens. But what baseball tells us is that there’s another game tomorrow, and there’s always another chance.

Michael O’Connell is a writer, editor, and educator who lives in Ann Arbor, MI. He is the author of Startling Figures: Encounters with American Catholic Fiction (Fordham University Press, 2023), and editor of Conversations with George Saunders (University Press of Mississippi, 2022). He is also co-editor of The Journal of David Foster Wallace Studies.

Why It’s Cool to Go to a Ballgame

By John Miller

Why might

Our brainy tribe of high-low dreamers

Big love Trinity thinkers

Belong for a few hours at a ballpark,

A public place you pay to pace in play?

The iPhone tickets on the ballpark app

Fences

Luxury boxes

The 2024 see-through Nike pants

The gamboling gambling

The hot dog merchants

And beer vendors who can’t take cash

All Caesar’s

On the other side of the ball:

The classical agora of the infield

And deep sea beyond second base

The green garden mystery that seduced me for life at seven

The spirits of players

And ours watching them, and us

Us, friends

Communities of believers

The joys of simple Newtonian physics, and asymmetry

Weird delight in quirky legalities (the balk! the infield fly rule!)

The glory of summer

What Bart Giamatti, a Yale renaissance lit professor once miraculously hired as commissioner of baseball, called

“this special, set-aside city” and

“a green expanse, complete and coherent, shimmering, carefully tended, a garden”

Point to odds of truth and beauty

Loving hearts and a walk-off sac fly

John W. Miller, a contributing writer at America Magazine, is the author of The Last Manager, which arrives in 2025 and tells the story of the famous Orioles manager Earl Weaver. It’s so much fun to watch managers give umpires a piece of their mind and no one was better at that than Weaver, which is why I’ll leave you with this video of him going at it in a game from 1980. WARNING: Prepare for baseball language!

This is a beautiful collection of thoughts that articulates exactly why I love baseball and really don’t care for any other team sports. (Were you at the first doubleheader match by any chance? What a great game!)